During my recent trip to Camiguin, one of the attractions that enthralled me the most was the Old Church Ruins in Bonbon, also known by its older name, Old Guiob (or Gui-ob) Church Ruins. Declared a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines,[1] it features just what its name suggests, the remnants of a 19th century church built during the Spanish colonial period. There is no stunning visual display here. To the introspective heritage traveler however, there is much to glean.

The Origin Story of Mt. Vulcan

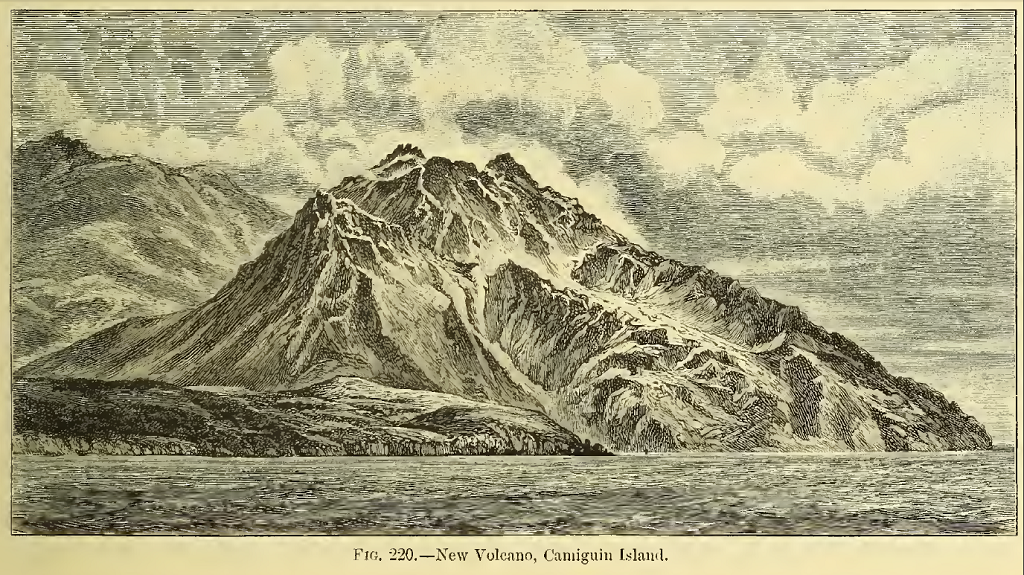

The old church’s story is invariably tied to the origin of Mt. Vulcan, also known as Mt. Volcan. Strangely, locals refer to it as the Old Volcano, when it is actually the most recent volcanic feature in Camiguin, a parasitic dome on the youngest volcano in the island, Mt. Hibok-hibok.[2] Although we have no local version of Pliny the Younger[3] to refer to for an account of the actual eruption of Mt. Vulcan, we do have old accounts closer to the date of the event.

According to the narrative of the H.M.S. Challenger, a British ship that visited Camiguin in 1875, the dome of Mt. Vulcan emerged in the months following July 1871.[4] Local writer, Vicente Elio pinned the date of the eruption on May 1, 1871,[5] but the current historical marker carries the date, May 13, 1871. Regardless of the differences in dates, all sources agree on one thing, the event was disastrous, thoroughly destructive, and life-altering for the people of Camiguin.

According to Elio’s monograph, 25,000 people from all over Camiguin fled to the neighboring islands of Bohol and Mindanao, leaving approximately just 200 people in the island. More than 200 individuals lost their lives. Catarman, which had 10,000 souls before the eruption had substantially lost its population.[6]

The number of people who stayed, rather than the number of deaths is more indicative of the state Camiguin, particularly Catarman, was in after the catastrophe. Both Elio and the Challenger account reveal the same outcome, Catarman was thoroughly destroyed.

Loss of Church and Life

Naturally, Catarman’s destruction also meant the ruin of it’s old church, rectory and bell tower. Close by is the town’s old cemetery, pushed a few meters under the sea by the same volcanic eruption. A lone cross marks the spot in the water where the departed still slumber, now aptly called Sunken Cemetery.

I must admit, my very first reaction at seeing the ruins was to marvel at how the wrath of nature spares none of the trappings of human empires, in this case, the physical church and its related structures. In my mind, the Catholic church edifice is one of the most definitive symbols of Spanish colonial power, and here, it crumbled when nature belched. Of course, beyond this rarefied thought lay a feeling of compassion for the people who were there whose lives were permanently impacted.

Anyone familiar with how Filipino communities were organized during the Spanish colonial period would realize the associated impact of losing a town church. At that time, the church was the literal and figurative core of community life. The church stood at the center of the main plaza, surrounded by the town’s administrative buildings, the tribunal, market, school and the houses of the town’s principal citizens. Every element of town life was literally under the bells of the church.[7][8] The loss of the town church therefore meant the loss of the heart of the community, its perceived spiritual and earthly focal point.

Catarman Relegated

The current marker beside the Old Church Ruins mentions Cotta Bato as the then capital of Camiguin. It’s safe to assume that since the ruins are in Catarman, that there was once such a place in Catarman. Both Elio and the Challenger narrative however, do not mention Cotta Bato, but take Catarman in its entirety, declaring it to be a prosperous town. Elio quoted Fray Calixto Gaspar (parish priest from 1883) declaring the town as the most flourishing before the eruption. By all appearances, Catarman was the preeminent town in Camiguin before 1871, with Mambajao a mere visita. [9]

Fray Gaspar did express hope that Catarman would one day prosper again owing to the abundance of its natural resources, fertile land and the zeal of its townspeople. To some extent, Catarman has risen again. Mambajao did at one point however, replace Catarman in prominence, and to this day is still considered the new capital of Camiguin.

Notes and References:

1. Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. “Camiguin church ruins, Sunken Cemetery declared National Cultural Treasures.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, December 17, 2018.

2. R. Castillo, Paterno & Janney, Philip & U. Solidum, Renato. (1999). Petrology and geochemistry of Camiguin Island, southern Philippines: Insights to the source of adakites and other lavas in a complex arc setting. Beiträage zur Mineralogie und Petrographie. 134. 33-51. 10.1007/s004100050467.

3. When Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 95 AD, Pliny the Younger was able to write an eyewitness account of the eruption that decimated the city of Pompeii as he sat across the Bay of Naples. “The Riddle Of Pompeii (Ancient Rome Documentary) | Timeline.” YouTube video, 49:51. “All3 Media International,” Aug 23, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=epZ1KT5cBrE.

4. T.H. Tizard et al. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76 (Edinburgh: Neil and Company, 1885), 652.

5. Vicente Elio y Sanchez, The History of Camiguin, (Quezon City: Atenedo de Manila, 1972), 2.

6. Ibid., p.128.

7. Raquel B. Florendo, Las Casas bajo de las campanas (Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2012), 5.

8. Luis H. Francia, A History of the Philippines From Indios Bravos to Filipinos (New York: The Overlook Press, 2010), 69.

9. Visita was the practice of the clergy during the Spanish colonial period of visiting communities located far from the main town central plaza complex and church. Ibid.

Recent Comments