My addiction to world history started at a young age, but I must admit, I did not always find Philippine history as appealing. This was mainly because the books and resources I could find about it as a child all read like the paper inserts in medicine cartons. I owe my current fascination for Philippine history to Ambeth R. Ocampo. The enduring appeal of his work is in his manner of storytelling. He takes down his long dead protagonists from their pedestals to tell their very human experiences.

Ocampo does more than tell interesting stories of course. He also digs deep, retracing faint footprints in recorded events and breaking treasured notions of a noble past, allowing us to discover and come to terms with half hidden truths about who we really are as a nation.

Digging into Controversy

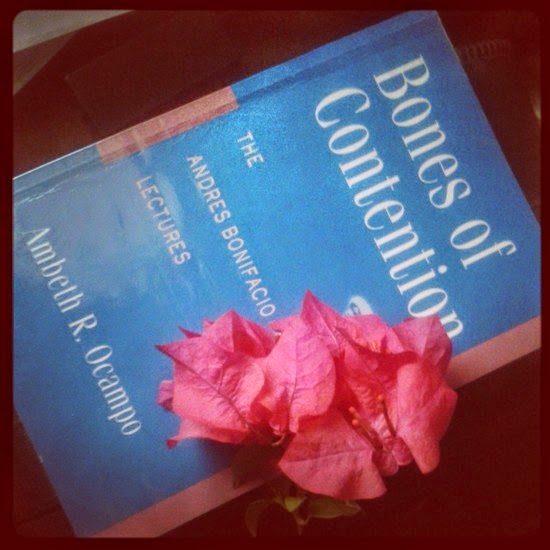

In his book, Bones of Contention: The Andres Bonifacio Lectures, I imagine Ocampo would have had to use all of his skills to write in length about one of Philippine history’s most difficult subjects. Although now firmly entrenched in our nation’s pantheon of heroes, Bonifacio’s story is rife with controversies, contradictions and uncertainties. This is to be expected considering his stature as the founder of the revolutionary movement. It would have been unlikely for him to want to leave a written record of his background, movements and whereabouts.

With the limitations inherent in such a subject, what does Ocampo manage to unearth for us?

Finding Some Bones

According to Ocampo’s research, Bonifacio’s bones may have been lost, found, lost again and in the end may have never been found at all.

In 1918, the alleged bones of Bonifacio were unearthed in Nagpatong, under the watchful eyes of Guillermo Masangkay who headed a committee in charge of finding his bones. It was from Masangkay that we hear of the story that Bonifacio was hacked to death, thereby incurring some damage to the skull.

The problem with this story is that it contradicts the account of Lazaro Makapagal, the Filipino officer who carried out the order to execute the Bonifacio brothers on a hill called Tala or close to it. The brothers, they say, were shot. His story puts the authenticity of the bones found in Nagpatong into question.

Where are the bones now? No one knows for sure. Ocampo writes that depending on the source cited, they may have been cremated, destroyed during the war when it was kept at the National Museum or stolen. In any case, they are now lost to us.

And Other Stories

Ocampo reveals more than the tale of Bonifacio’s bones, he also details events in the lives of people who at some point intersected paths with Bonifacio. Among other things, Ocampo reveals:

1. Mabini’s allegations that during the war, there were cases of Filipinos raping Filipinas, shattering our belief of our forefathers’ entirely noble struggle for freedom. Ocampo interprets one recorded account as proof that Gregoria de Jesus, Bonifacio’s wife, was herself a rape victim.

2. The prolonged feud that ensued when Aguinaldo did not support Quezon’s policy of non-cooperation with the Americans. The disagreement escalated to such extreme degrees that it may have even resulted in the suspension of Aguinaldo’s life pension.

3. Aguinaldo was perhaps the most high profile squatter in Philippine history. The former president apparently did not own the land he lived on. The estate was eventually put up for sale, at a time when the feud with Quezon was still raging.

4. Quezon may have used Bonifacio’s alleged bones to implicate Aguinaldo in Bonifacio’s execution. This would have allowed Quezon to gain an upper moral hand over his nemesis.

5. Although the Cry of Pugad Lawin is officially recognized, some sources contend that the “cry” could have happened elsewhere, possibly in Balintawak, Kangkong or Pasong Tamo.

6. The Great Plebian may be a misnomer. Bonifacio may not have been as poor and uneducated as some history textbooks imply. He was well-read and earned a decent living. He was initiated into masonry, an institution that did not accept those who were coarse or impoverished.

7. The Malolos Banquet after the declaration of Philippine independence featured French cuisine to show the world that Filipinos were civilized enough to deserve independence.

8. Reading may not have been Aguinaldo’s favorite hobby. An old man by the 1950s, he revealed that he had not even read Rizal’s Noli and Fili because his Spanish was inadequate. In contrast, Bonifacio is believed to have read Rizal’s books and many others.

A Glimpse Into Ocampo

Ocampo also divulges a little about himself in his book. He showed some vulnerability by revealing that he wept over Bonifacio’s tragic story. His most surprising revelation however, is his having acquired critics in the course of his work. Why do some disapprove of Ocampo? Is it because his manner of educating opens more cans of worms, presents more questions than answers and demolishes acceptable history?

But Ocampo’s style is exactly what we need to educate future researchers, historians and Filipinos. The key to developing more historically aware citizens is to draw their interest and then invite them to explore deeper on their own. Ocampo teaches us that history is not static and that many facts are actually uncertainties, hence the need to constantly question and discover. Ocampo leaves us with the impression that even his stories may have to be revised in the future.

When was bones of contention written?