It isn’t an exaggeration to say that no other work of literature is as well known in the Philippines as Noli Me Tangere. If you’ve ever spent some years in a Filipino school, even at the elementary level, you would have heard of the book and its author, the country’s most famous son, Jose Rizal.

Jump directly to the index here.

Discovering the Noli

It is only fitting that the Noli should be taught so diligently in our educational institutions. It, along with Rizal’s other works and his own person, is after all, credited in part with awakening the consciousness of a nation. To this day, it remains an enduring rebuke to tyranny, corruption, and more importantly, the social structures that deify a people’s borrowed foreign skins and reinforce their perceived inferiority.

It is however, perhaps because of the mandatory nature of the Noli’s introduction to our youth that some develop, at the very least, indifferent feelings towards it, which is a shame. More than being a vessel from which students are forced to fish some bits of ponderous wisdom, it is also a wonderfully delightful piece of literature. Beyond its critique of society, the Noli should also be appreciated for its biting humor, its rich imagery, and its depth of feeling.

I was lucky, I had a Mdm. Alesna, who taught the Noli with such infectious vigor, we all imagined we were in San Diego or Binondo. I was luckier still for having experienced the Noli fabulously brought to life on stage by the CCP. To this generation, John Arcilla is Heneral Luna, but to me, he will always be my Ibarra. It is by this serendipitous set of circumstances that forever made me a Noli enthusiast. But what of others who may not be so fortunate?

The Noli Project

While I do not profess to have created anything as inspiring as my sources of inspiration, it is my hope that my handiwork may at least awaken a germ of curiosity among the indifferent. Hence, I offer what I fondly call my Noli Project to the Filipino youth who are about to embark on a literary journey of discovery, to my fellow Filipinos abroad who may not have discovered the Noli at all, and to the Filipino at heart who seek to understand and appreciate the many facets and layers of our national identity and origin story.

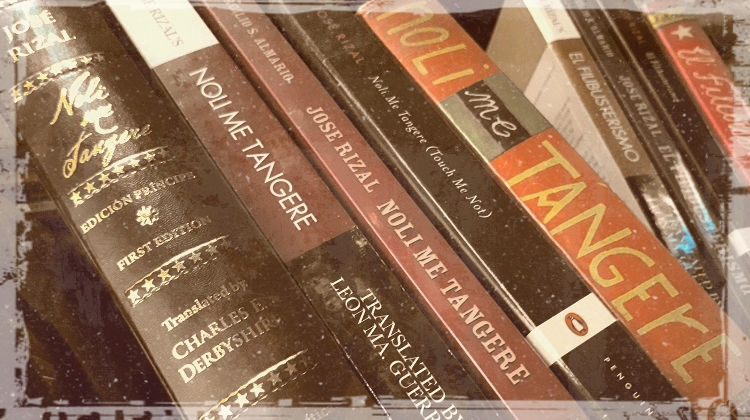

For this project, my primary source is Charles Derbyshire’s English translation, supported by a number of other translated versions[1-5]. Each chapter summary is followed by a video clip containing my illustrations of the audiobook (courtesy of Librivox) of Derbyshire’s text. Included is a special retranslation of what Rizal initially included as Chapter 25, Elias and Salome, and which he excluded from the first printed version.[6]

It is unfortunate that I have had to settle on English as my primary medium for these summaries, but I feel that at this moment in time, it is the language with the widest reach across continents and across generations among my target audience. But anyone who may be more inclined to read the full, original Spanish version[7] can find the text put together with Derbyshire’s translation in the critical edition by Isaac Donoso Jimenez. If you wish to read the Filipino translation there is one by Pascual H. Poblete or by National Artist Virgilio S. Almario.

Noli Me Tangere Chapter Summaries

The chapter summaries are organized by groups of 5 chapters each. Click each link below to access the summaries.

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 1-5 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 6-10 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 11-15 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 16-20 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 21-25 Summaries, Including ‘ Elias and Salome’

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 26-30 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 31-35 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 36-40 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 41-45 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 46-50 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 51-55 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 56-60 Summaries

- Noli Me Tangere Chapters 61-64/Epilogue Summaries

Read El Filibusterismo chapter summaries here.

References and Notes:

1. Rizal, Jose. Noli Me Tangere. Translated by Leon Ma. Guerrero. Manila: Guerrero Publishing, Inc., 2010.

2. Rizal, Jose. Noli Me Tangere. Translated by Virgilio S. Almario. Quezon: Adarna House, Inc., 2011.

3. Rizal, Jose. Noli Me Tangere. Translated by Harold Augenbraum. USA: Penguin Group, 2006.

4. Rizal, Jose. Noli Me Tangere. Translated by Ma. Soledad Lacson-Locsin. Makati: Bookmark, Inc., 1996.

5. Rizal, Jose. Noli Me Tangere. Critical Edition by Isaac Donoso Jimenez. Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, 2011.

6. School references traditionally explain the removal of the ‘Elias and Salome’ chapter as owing to Rizal’s financial difficulties, as a shorter novel costing less to print. Donoso mentions in his notes however, that no actual explanation from Rizal has been preserved to account for the removal. Hence, Rizal’s money problems is really more of a hypothesis by historians. A second hypothesis is the chapter being inconsequential to the overall narrative. Isaac Donoso Jimenez, Filipiniana Classica: Jose Rizal Noli Me Tangere Edicion Critica (Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, 2011), 778.

7. Historian Ambeth Ocampo suggests that the ideal way to consume Rizal’s work is to read then in their original Spanish texts. Ibid., p.x.

Recent Comments